Emojis: A Global Phenomenon

Written by Éamon Chawke | September 10, 2019

17 July is noteworthy for a number of reasons. In 1048, it was the date on which Damasus II was elected pope. In 1821, it was the date on which the Kingdom of Spain ceded the territory of Florida to the United States. In 1955, it was the date on which Disneyland was opened by Walt Disney in Anaheim, California. And last but not least, since 2014, it is the date on which we now celebrate World Emoji Day. With now more than 2,800 emoji symbols, emojis have become a global phenomenon!

Evolution of the emoji

Emojis were first created in Japan in the 1990s and since then the numbers and genres of emojis have expanded significantly to include facial expressions, common objects, places and animals.

In 2010, certain emojis were incorporated into the Unicode. The Unicode is the standard system for indexing characters maintained by the Unicode Consortium. The Unicode Consortium is a non-profit body that periodically publishes the Unicode (which now includes emojis) and it selects the emojis that will be used globally (often as a result of submissions from the public who present the case for the inclusion of certain emojis e.g. due to cultural relevance).

The inclusion of emojis in the Unicode contributed to the increased use of emojis outside of Japan and also allowed for emojis to be standardised across different operating systems. The popularity of emojis increased further as a result of their inclusion in the Apple iPhone.

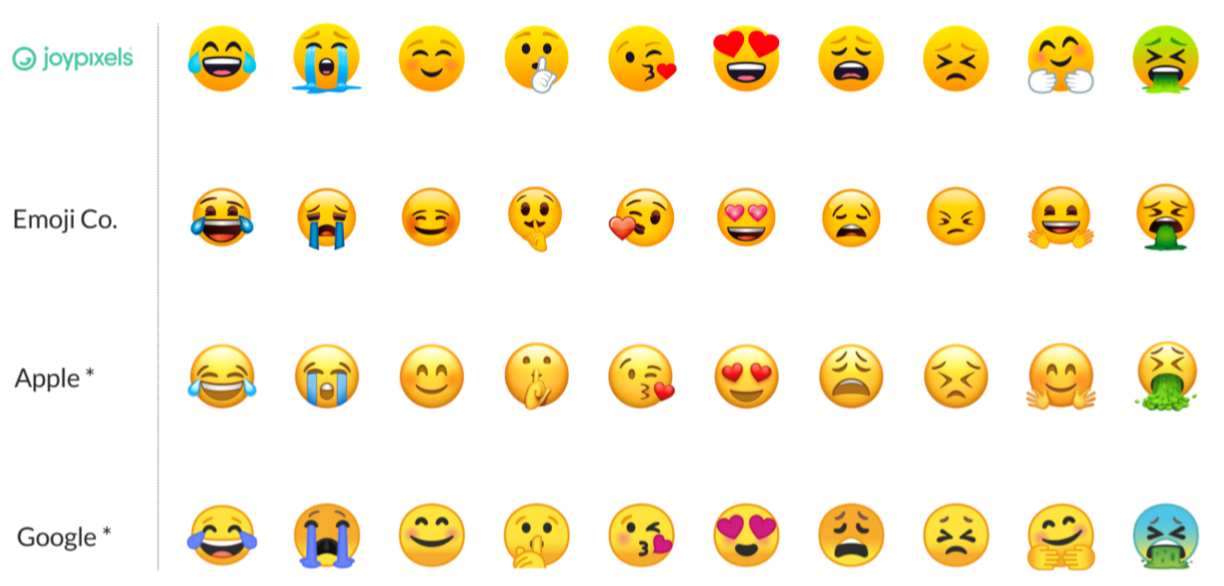

Subsequently, a number of companies, including Google, Facebook, Samsung and HTC have developed their own versions of emojis.

Can emoji artwork be protected by law?

This gives rise to a number of interesting questions from an intellectual property perspective: do all these different companies own the copyright in their own emojis; are emojis even capable of being protected by copyright; aren’t all emojis basically the same?

First, the default position under English law is that copyright in an artistic work vests automatically and immediately in the ‘author’ (i.e. the creator of the artistic work) or in his/her employer (where the artistic work was undertaken by an employee in the course of his/her employment). It follows therefore that all these different companies can in theory own the copyright in the emojis created by the artists and designers employed by them.

Second, in order to qualify for copyright protection, the artistic work must be original. However, ‘originality’ in the copyright sense does not mean that the artistic work must be inventive, novel or unique (or indeed that it must have any artistic merit!). Copyright law is concerned with the originality of expression, rather than originality of ideas. Therefore, originality in the copyright sense simply means that the artistic work must be the result of the author’s own skill, labour and judgement. In other words, it must not be copied. The originality threshold under English law has also been set at a very low level (coupons, calendars and competition cards have all been found to be sufficiently original for the purposes of attracting copyright protection).

Taking all of the above into consideration, most if not all emojis are likely to be sufficiently original to benefit from copyright protection as artistic works, provided of course that they have not been copied for earlier artistic works.

Third, emojis are not basically all the same. There may of course be multiple versions of the same smiling face or animal or everyday object or whatever, but remember that copyright law is concerned with the originality of expression, and not originality of ideas, so as long as each of those versions is the result of the artist’s own skill, labour and judgement, it will be sufficiently original to be protected by copyright.

So emoji artwork is free to use then?

Yes and no. There is nothing preventing a person from using emojis in the ordinary course of their communications on their phone, tablet or computer. There are also certain companies such as JoyPixels who grant individuals a free licence to use their emoji artwork for personal, non-commercial purposes.

However, companies wishing to commercialise emoji artwork generally need a licence to use the artwork from the copyright owner. For example, JoyPixels grants companies licences to use its emoji artwork for commercial purposes via a global network of licensing agents.

JoyPixels was founded in September 2014 as a free open source emoji set, and was the first of its kind. Its success was immediate, and over the years has evolved from a humble hobby into a leading enterprise level emoji provider.

Born Licensing is the appointed global master licensing agent for JoyPixels and manages the licensing business across consumer products, advertising and broadcast. They’ve recently signed deals with Sky Mobile, MINI, Morrison’s, booking.com and Channel 4 who have all licensed JoyPixels emojis in their advertising and marketing material.

Can emoji words be protected by law?

Emoji symbols are protectable as copyright works but words, phrases, signs, symbols and logos are also capable of being protected as registered trade marks. The word emoji and variations of the word emoji have already been registered by various different companies. On the EU trade marks register alone, the words ‘emoji’, ‘emojidom’, ‘femojis’, ‘emoji blast’, ‘emojitones’, ‘emojipedia’ and ‘facemoji’ have all be registered by different companies.

A registered trade mark is a very valuable asset because it allows the owner to prevent third parties from using a mark/sign which is identical or similar to the registered trade mark in relation to the goods or services for which trade mark protection has been granted.

However, registered trade mark protection has its limits. For example, the owner of a registered trade mark cannot prevent third parties from using the trade mark if it is necessary to use the trade mark to describe the characteristics of the goods and services in question. In other words, descriptive use is permitted. For another example, the owner of a registered trade mark cannot prevent third parties from using the trade mark if it is necessary to use the trade mark to identify or refer to the goods of the registered trade mark owner. In other words, referential use is permitted.

Finally, registered trade marks have in the past, in certain circumstances and in certain territories, become generic through use over time and as a result lost their trade mark protection. Trade marks like escalator (Otis Elevator Company) and flip phone (Motorola) were originally legally protected, but subsequently lost legal protection as trade marks because the consuming public and commercial competitors used the trade marks as a generic terms to describe the relevant products.

So emoji words are free to use then?

Yes and no. There is nothing preventing a person from using the word ‘emoji’ (and variations of the word emoji such as those referenced above) if the purpose of that use is to describe the characteristics of goods or services (e.g. the t-shirt with the emoji) or to refer to the goods or services of the trade mark owner (e.g. The Emoji Movie).

However, companies wishing to use the word the word ‘emoji’ (or variations of the word emoji such as those referenced above) should consider the whether the word in question is protected as a trade mark in the classes of goods and services in question and in the territory in question, and consider whether the proposed use might give rise to trade mark infringement without an appropriate licence from the trade mark owner (i.e. not covered by the descriptive use and referential use exceptions described above).

Briffa comment

One thing is clear: emojis are now a global phenomenon and, despite their humble beginnings, have become incredibly commercially valuable. Intellectual property rights like copyrights, trade marks and registered designs are the assets that capture that value and allow for commercialisation through licensing.

Briffa are experts in all aspects of intellectual property law and practice, including non-contentious matters such as trade mark prosecution and copyright licencing, and contentious matters such as trade mark and copyright infringement. If you would like to discuss any intellectual property matter with one of our specialist lawyers, please do not hesitate to contact us on info@briffa.com or 020 7096 2779.

Written by Éamon Chawke, Solicitor